What If: Antwerp Falls During the Battle of the Bulge

- EA Baker

- Dec 30, 2025

- 9 min read

Updated: Jan 21

By December 1944, Nazi Germany stood on the brink of defeat. In the West, Allied armies had broken out of Normandy, liberated Paris, and reached the German frontier. In the East, the Red Army had destroyed Army Group Centre during Operation Bagration and was preparing for its final drive into the Reich. German oil production was collapsing under sustained Allied bombing, the Luftwaffe had lost air superiority, and the Wehrmacht was scraping together teenagers and elderly men to fill its ranks.

And yet, Adolf Hitler ordered one last major offensive in the West: Operation Wacht am Rhein (Watch on the Rhine). It would become known as the Battle of the Bulge. Its goal was nothing less than the seizure of Antwerp, the most important Allied port on the continent. Historically, the offensive failed spectacularly. But what if it had not? What if German forces had reached Antwerp and temporarily taken the port?

This article explores that counterfactual by grounding it firmly in historical realities—logistics, force structure, command decisions, and Allied responses—rather than wishful thinking. It also makes clear where plausibility ends and fantasy begins.

Antwerp and the Strategic Stakes

Antwerp was not merely a symbolic objective; it was the logistical keystone of the Allied campaign in Northwest Europe. After its capture by British forces on 4 September 1944, the port—once the Scheldt estuary was cleared in November—became capable of handling more than 40,000 tons of supplies per day, compared to the much longer and increasingly strained supply routes running from the Normandy beaches and Cherbourg. By December 1944, Antwerp was sustaining the bulk of the British 21st Army Group and an increasing share of U.S. forces operating in Belgium and the Netherlands.

From a German perspective, the port represented the single most important Allied logistical vulnerability west of the Rhine. Hitler believed that its seizure would paralyze Allied operations, separate British and American forces geographically, and force a negotiated settlement in the West. Senior German commanders—including Rundstedt, Model, and Manteuffel—understood the port’s importance but consistently warned that the forces available could not reach it, much less hold it, given fuel shortages, Allied air superiority, and the depth of Allied reserves. The strategic value of Antwerp was real; Germany’s ability to exploit that value was not.

The Historical Failure of Wacht am Rhein

Operation Wacht am Rhein began on 16 December 1944 with approximately 30 German divisions, including 11 panzer and panzergrenadier divisions, concentrated in the Ardennes. On paper, this represented a formidable force. In practice, many of these divisions were understrength, short of trained replacements, and critically deficient in fuel. German planning assumed that armored spearheads would capture sufficient Allied fuel stocks to sustain the advance—an assumption that reflected desperation rather than logistics.

Initial surprise enabled German units to breach thinly held American lines, particularly in the U.S. VIII Corps sector. Yet the offensive ran into systemic constraints almost immediately. The Ardennes road network could not support sustained mechanized traffic, producing severe congestion that delayed armor and fuel columns alike. German formations advanced on rigid timetables that left little margin for delay. American delaying actions—most notably at St. Vith and Bastogne—forced German units to divert strength and time. Once the skies cleared after 23–24 December, Allied air forces flew many sorties, systematically attacking German bridges, road columns, and supply depots, immobilizing much of the offensive.

Most decisively, German forces never reached the Meuse River in operational strength. Without a Meuse crossing, the drive to Antwerp—more than 200 miles from the German start lines—was operationally impossible.

The Necessary Point of Divergence

Any scenario in which Antwerp falls requires divergence well before December 1944. Tactical refinements alone cannot overcome Germany’s late-war structural deficiencies.

The first requirement is a less catastrophic collapse of Germany’s fuel system. Allied attacks on synthetic fuel production in mid-1944 reduced output from approximately 175,000 tons per month in early 1944 to less than 20,000 tons by September, a decline Albert Speer, the Minister of Armaments and War Production, later identified as decisive. In this counterfactual, the oil campaign still succeeds, but with less complete destruction, leaving Germany with modestly higher operational reserves entering the winter, enough to fuel a short exploitation phase rather than a prolonged campaign.

The second requirement is a less devastating outcome on the Eastern Front. Operation Bagration historically destroyed or crippled roughly 28 German divisions and eliminated Army Group Centre as an effective fighting force. A scenario in which German forces withdraw earlier and avoid large-scale encirclement preserves additional armored and mechanized formations. These formations are still outnumbered and pressured, but they are not annihilated, allowing Germany to concentrate slightly greater strength in the West without inviting immediate collapse in the East.

A Different Ardennes Campaign

Within these altered strategic constraints, German execution of the Ardennes offensive must also change. Bastogne, historically bypassed in the early days of the offensive, becomes a primary operational objective. Its road network controlled seven major routes through the Ardennes and was essential for sustaining any westward advance. In this scenario, German commanders allocate sufficient infantry and armor to overwhelm the initial American defense, securing Bastogne by 18 December, before the arrival of major reinforcements from the 101st Airborne Division.

The capture of Bastogne materially improves German logistics. Supply columns move with fewer interruptions, congestion is reduced, and fuel reaches forward units more consistently. The capture of intact Allied fuel dumps near Stavelot and Spa compounds this advantage. Historically, German units seized only limited quantities before Allied counterattacks or demolitions intervened. Here, German forces capture fuel on the order of hundreds of thousands of gallons, sufficient to sustain armored spearheads for several additional days of high-tempo operations.

Crossing the Meuse

The Meuse River represents the decisive operational barrier. German planning assumed it could be crossed within days of the offensive’s start, yet historically, German spearheads never reached it in force. In this counterfactual, reduced delays and improved logistics allow advance elements to reach the Meuse by 22–23 December.

Engineer units, operating under continued poor weather that limits Allied air activity, succeed in either seizing a bridge intact or rapidly emplacing pontoon bridges near Dinant or Givet. This success is aided by Allied misjudgment: British XXX Corps, historically positioned specifically to block a Meuse crossing, arrives later than anticipated or concentrates on the wrong sector. The crossing does not represent German dominance so much as the exploitation of a narrow window created by speed, weather, and imperfect Allied coordination.

The Fall of Antwerp

With a bridgehead established west of the Meuse and Allied air power still partially constrained by weather, German armored columns drive northwest toward Antwerp. Defenses around the city are limited; its rapid capture in September 1944 meant that no extensive field fortifications had been constructed. By late December or early January, German forces reach Antwerp and seize the port facilities. Allied demolition efforts damage docks and cranes, reducing throughput but failing to deny the port entirely.

The fall of Antwerp represents a severe operational shock, but not a decisive strategic reversal. German forces around the city are operating at the extreme limit of their logistical endurance, with fuel and ammunition stocks rapidly dwindling.

Consequences and Limits

The immediate effects of Antwerp’s temporary loss are substantial. Allied supply flows into Northwest Europe are sharply reduced, forcing an operational pause while alternative routes are expanded and port facilities are repaired. Political shock reverberates in London and Washington, and Allied planners reassess their timetable for the final advance into Germany.

Yet structural realities reassert themselves quickly. German forces holding Antwerp are dangerously overextended, reliant on fragile supply lines across the Meuse. Once the weather improves, Allied air forces isolate the battlefield, destroying bridges and interdicting rail and road networks. With overwhelming numerical superiority—by early 1945, the Western Allies fielded more than 4 million men in Europe—Allied ground forces launched coordinated counterattacks. Within weeks, Antwerp is retaken. Though damaged, the port resumes operations after repairs, as it historically did following German V-weapon attacks.

Critically, developments in the West do nothing to halt the Red Army. In January 1945, Soviet forces launched the Vistula–Oder Offensive, advancing roughly 300 miles in three weeks and reaching the Oder River, less than 50 miles from Berlin. Germany’s strategic defeat remains inevitable regardless of Antwerp’s temporary loss.

How Close Germany Could Realistically Come

Absent the favorable convergence of fuel availability, rapid Bastogne capture, successful Meuse crossings, and extended poor weather, Germany’s maximum realistic achievement in the Ardennes remains limited. A deeper salient, heavier Allied casualties, and a temporary delay in Western operations were plausible outcomes. A sustained crossing of the Meuse and a drive to Antwerp were not.

Attritional realities overwhelmingly favored the Allies. German losses during the historical Battle of the Bulge—approximately 100,000 casualties and thousands of irreplaceable vehicles—could not be offset. Any deeper success would only accelerate the exhaustion of Germany’s remaining mobile forces.

A Mirror Image of Market Garden

Operation Wacht am Rhein invites direct comparison with Operation Market Garden, the Allied airborne–armored offensive conducted in September 1944. Though carried out by opposing sides, both operations reflected a similar form of strategic overreach, rooted in optimism about speed, surprise, and enemy fragility.

Market Garden sought to bypass the German frontier defenses by seizing a chain of bridges over the Maas, Waal, and Lower Rhine, enabling a rapid thrust into the Ruhr. Its success depended on airborne forces holding bridges long enough for a single narrow ground corridor to be forced forward by XXX Corps. German resistance proved stronger and more resilient than anticipated, delays compounded, and the final bridge at Arnhem remained in German hands. The operation failed to achieve its strategic objective, but the Allies retained overwhelming material superiority and the initiative. The failure delayed—but did not end—the Allied advance.

Wacht am Rhein represented a similar gamble under far worse conditions. Like Market Garden, it relied on narrow axes of advance, optimistic assumptions about enemy reaction time, and the belief that bold operational maneuver could compensate for logistical fragility. Unlike the Allies, however, Germany lacked the reserves to absorb failure. While Market Garden failed, the Allied advance continued, though at a slow pace; the Ardennes offensive failed backward, consuming Germany’s last operational panzer reserves and accelerating its strategic collapse.

Both operations demonstrate a shared lesson of late-war campaigning: when logistics, air superiority, and attritional balance are unfavorable, operational daring cannot substitute for material reality.

Final Assessment

The counterfactual fall of Antwerp during the Battle of the Bulge is conceivable only within an extremely narrow and historically implausible set of conditions. It requires a Germany that enters the winter of 1944–45 with greater fuel reserves, fewer catastrophic losses on the Eastern Front, and a more coherent concentration of armored forces than it historically possessed. Even then, Antwerp’s capture would represent a temporary operational success rather than a strategic turning point.

The decisive factors of the war, industrial capacity, manpower, air superiority, and the momentum of the Red Army, remain unchanged. The Western Allies could absorb the temporary loss of a port; Germany could not absorb the loss of its last mobile reserves. Antwerp’s fall would disrupt Allied logistics and delay operations, but it would not prevent the Soviet drive to the Oder, nor would it avert the Reich's collapse in the spring of 1945.

Ultimately, Antwerp illustrates the central tragedy of Germany’s late-war strategy. Clear-eyed operational analysis was subordinated to political fantasy, and realistic defensive options were discarded in favor of a gamble that could not succeed on its own terms. Even in its most favorable counterfactual form, the seizure of Antwerp delays defeat—it does not alter it.

The Battle of the Bulge, whether it fails historically or succeeds temporarily in this scenario, remains what it truly was: not a last chance to win the war, but the final confirmation that Germany had already lost it.

Sources

Atkinson, R. (2013). The guns at last light: The war in Western Europe, 1944–1945. New York, NY: Henry Holt.

Beevor, A. (2015). Ardennes 1944: Hitler’s last gamble. London, UK: Viking.

Citino, R. M. (2012). The Wehrmacht retreats: Fighting a lost war, 1943–1945. Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas.

Glantz, D. M., & House, J. (2015). When titans clashed: How the Red Army stopped Hitler (Rev. ed.). Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas.

Keegan, J. (1989). The Second World War. New York, NY: Viking.

MacDonald, C. B. (1984). A time for trumpets: The untold story of the Battle of the Bulge. New York, NY: William Morrow.

Tooze, A. (2006). The wages of destruction: The making and breaking of the Nazi economy. New York, NY: Viking.

Weigley, R. F. (1981). Eisenhower’s lieutenants. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

Images

Unknown. (1944). US POWs of the 99th Infantry Division, 17 December 1944, guarded by German 3rd Parachute Division [Photograph]. Wikimedia Commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:0e16843b7e2648e68c92f4094c4f239c--the-battle-division.jpg

Dymetrios. (2024). The battleground 15 Dec 1944 [Map]. Wikimedia Commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:The_Battleground_15_Dec_1944.svg

U.S. Army. (1944). The 101st Airborne troops move out of Bastogne after ten days under siege [Photograph]. Wikimedia Commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:101st_Airborne_troops_move_out_of_Bastogne.jpg

U.S. Army Signal Corps. (1944). German troops at Battle of the Bulge, 16 December 1944 [Photograph]. Wikimedia Commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:German_troops_at_Battle_of_the_Bulge,_16_December_1944.jpg

Calvano, T. V. C. (1944). German Tiger II tank in Stavelot, Belgium, 21 December 1944 [Photograph]. Wikimedia Commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:German_Tiger_II_tank_in_Stavelot,_Belgium,_21_December_1944_(111-SC-198115).jpg

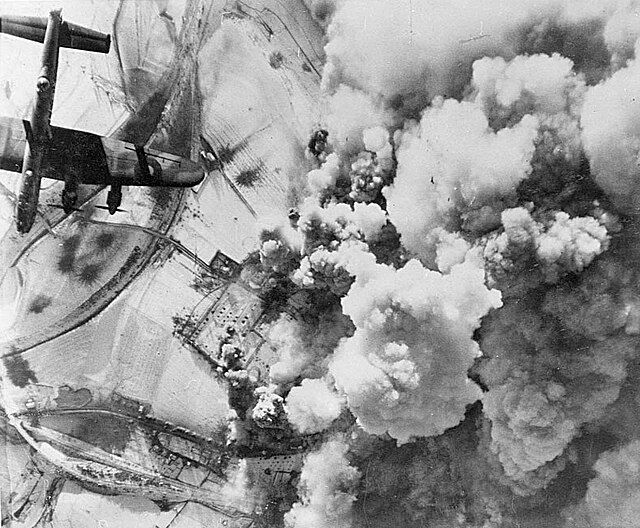

Royal Air Force / U.S. Army Signal Corps. (1944). RAF attack on St. Vith, Belgium, 26 December 1944 [Photograph]. Wikimedia Commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:RAF_attack_St._Vith_26_Dec_1944.jpg

U.S. National Archives. (n.d.). “We were getting our second wind now and started flattening out that bulge. We took 50,000 prisoners in December alone.” [Photograph]. Wikimedia Commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:%22We_were_getting_our_second_wind_now_and_started_flattening_out_that_bulge._We_took_50,000_prisoners_in_December_alone.%22_-_NARA_-_535976.tif

Comments